(If you haven’t read parts one, two, and three, you’ll want to do so before diving in to this post.)

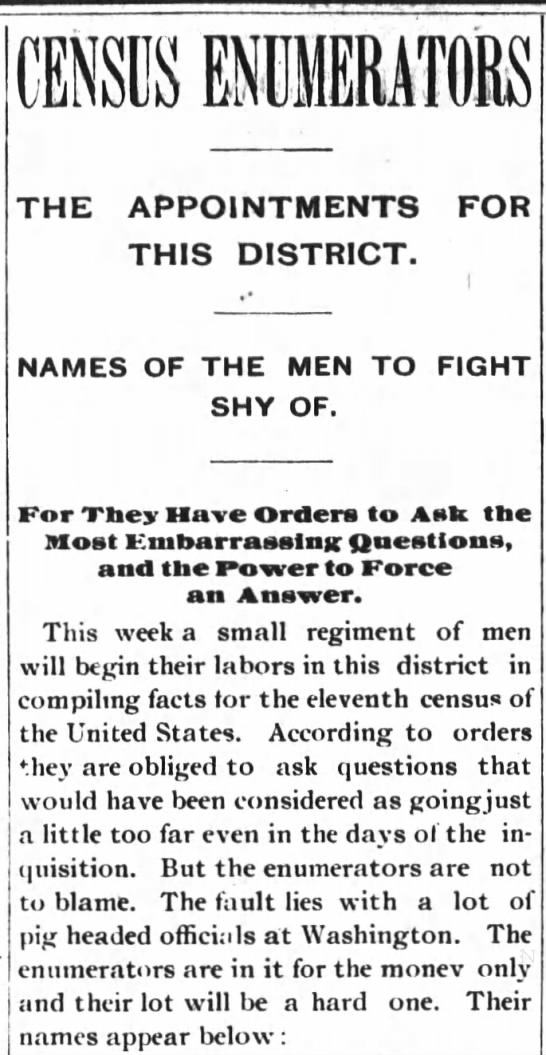

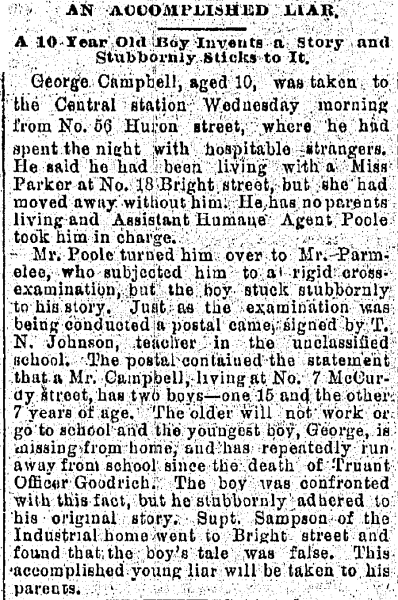

When Mary (Nagle) Campbell died from childbirth complications on 31 March 1888,1 her widower James Campbell was left to raise their five children alone. Within a year, the three elder boys (especially George) were on the radar of the local authorities. In May of 1889, both the Plain Dealer and the Leader reported on George Campbell’s miscreant behavior.

Although both articles and the teacher who exposed young George’s lies got some details about the family incorrect—namely that George’s parents were alive when in fact only one of them was living—there’s enough accurate information about the Campbells of No. 7 McCurdy Street to infer that James’s third eldest son, George (born in 1879), was the titular “bad boy” and “accomplished young liar.” George ran away again the very same night he was marched home by Agent Poole and remained missing for at least a week.

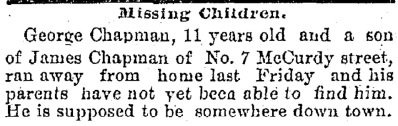

Twelve-year-old Joseph was apparently in trouble as well, and the authorities wanted to send both boys to the House of Refuge. Whether they were actually incarcerated or not is not yet known, but what is known is that a year later, in April of 1890, George ran away again.

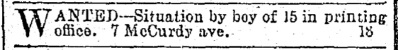

The fifteen-year-old boy mentioned in “An Accomplished Liar” is probably eldest son Charles, who is almost certainly the subject of a “situation wanted” classified advertisement from March 1889, which seems more likely to have been placed by James than by Charles who, according to teacher T.N. Johnson anyway, “would not work.”

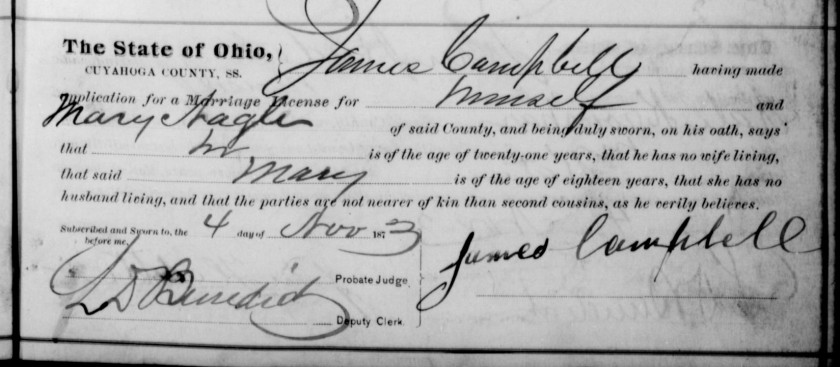

Between the two younger children, Martha Jane (Jennie) and William (who turned seven and four respectively in 1890), and the apparently out-of-control older boys (especially George), James clearly couldn’t do it all alone. Help arrived on 14 June 1890, when James married his second wife, Fannie “N. Dean.” (Fannie didn’t have a middle name, and “Dean” was not her surname–but that’s all coming up in part five).

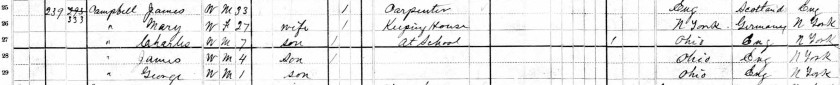

The loss of the 1890 United States Census is especially acute when it comes to the Campbell family, as it’s the one enumeration year in which all of the Campbell children should have appeared with their father in one household–although it may or may not have included Fannie since she and James were married twelve days after that year’s official census date, 2 June 1890.8 Luckily, the census isn’t the be-all end-all of genealogical records, especially in a city like Cleveland.

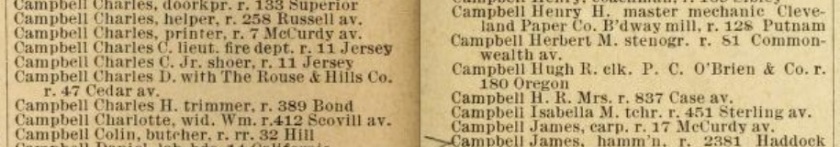

By 1891, Charles Campbell appears to have settled into work as a printer. He’s listed as such in the 1891/1892 Cleveland City Directory, residing at 7 McCurdy av. James Campbell, carpenter, is listed on the very next page, although his entry has him residing at 17 McCurdy instead of 7 McCurdy.

Joseph Campbell first appears in his own right in the 1895/1896 edition of the directory, as a teamster residing at 56 McCurdy Ave. James (still a carpenter) and Charles (still a printer) are also listed at 56 McCurdy Ave in 1895/1896.10

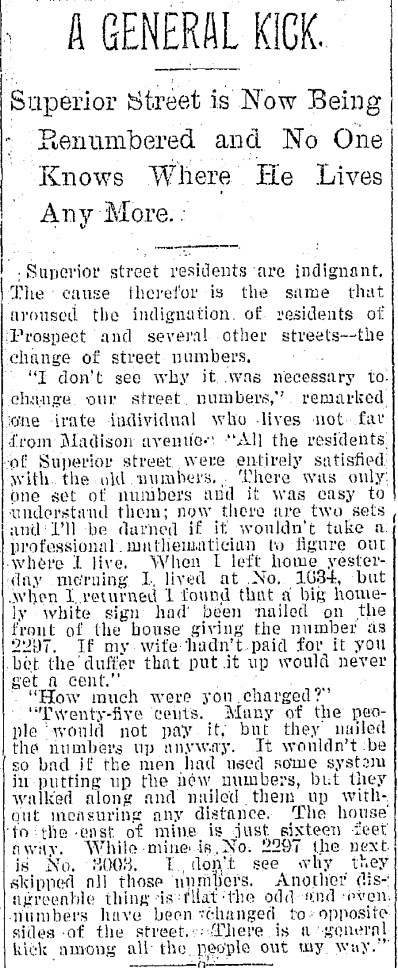

No, the family didn’t move down the street. Cleveland’s house and street numbering system was extremely inconsistent until 1906,11 much to Clevelanders’ consternation. For example:

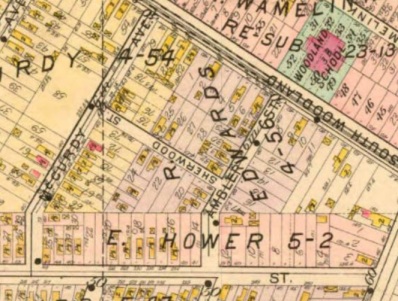

The Campbells’ shifting house number is down to the non-standardized and inconsistent numbering system, and not because the Campbell family was moving up and down McCurdy from house number 7, to 17, to 56–although that would have been a good trick, considering how McCurdy was (and still is) a very short street:

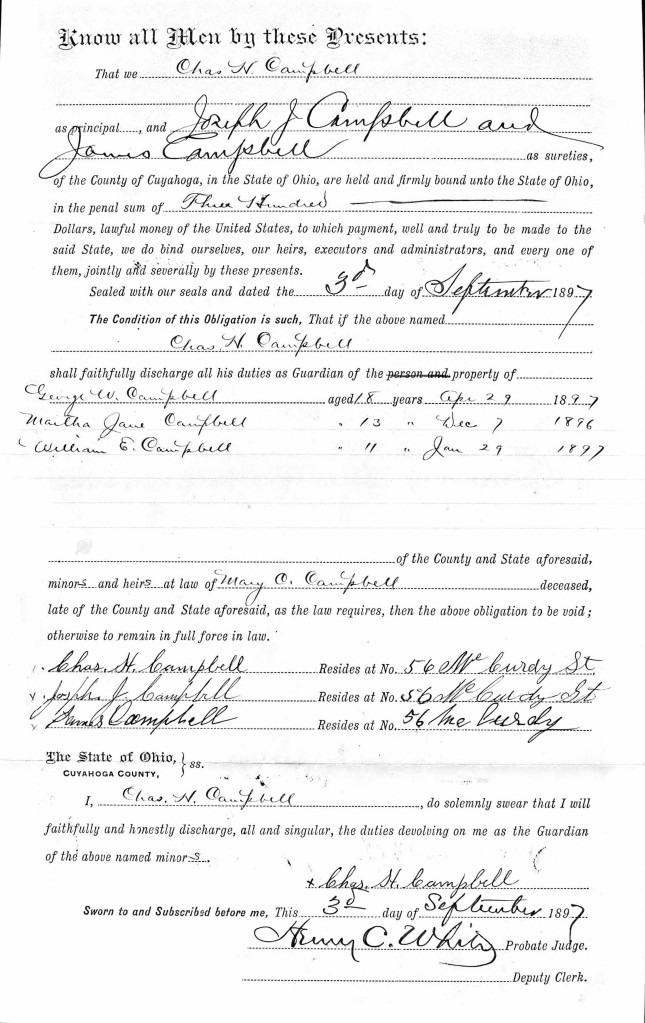

On 27 August 1896, Charles Henry Campbell married Inga Theresa Simmons.14 A year later, on 3 September 1897, he applied to the probate court for guardianship of the estate of his younger siblings, George W., Martha Jane, and William E. Campbell, who were still minors. James and Joseph J. Campbell served as sureties on the guardian bond.

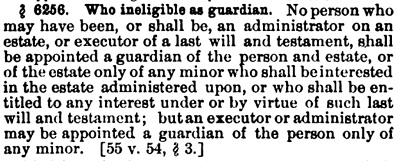

Wait. What estate? Let’s back up. In 1883, James and his first wife, Mary, bought property on McCurdy Ave.16 When Mary died intestate (without a will) on 31 March 1888, both her widower James and her children inherited portions of her share of ownership. The minor children couldn’t legally make decisions about their share of the property, but a guardian appointed on their behalf could. So why would the elder brother, Charles, become guardian of his siblings’ estate as opposed to their father, James? Well, according to the 1897 probate code of Ohio, James was ineligible.

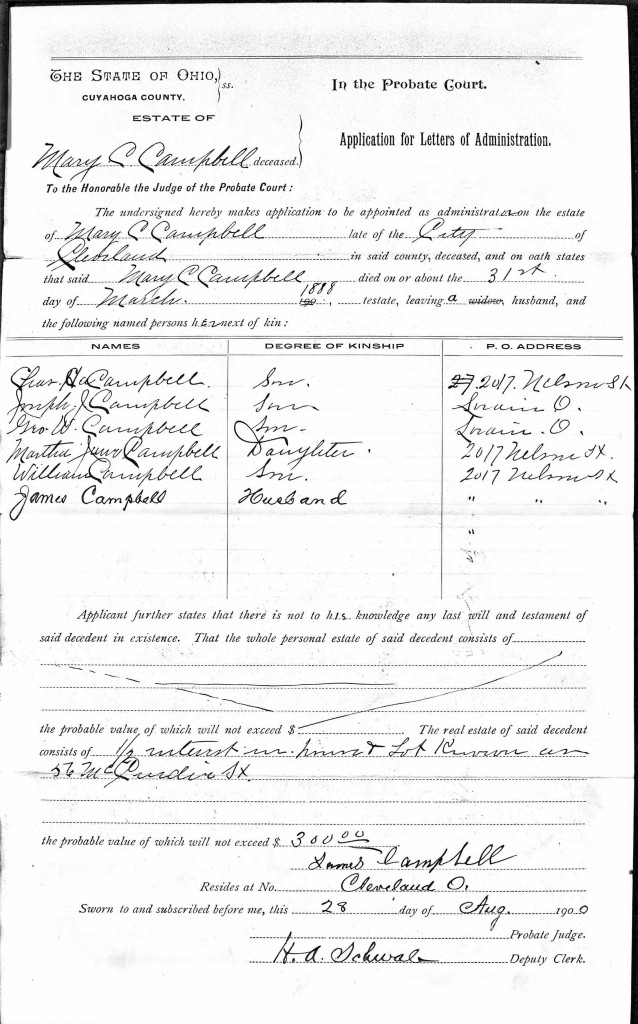

On 28 August 1900, James Campbell applied for letters of administration on Mary Campbell’s estate, thus rendering him ineligible to be guardian of the minor Campells’ interest in the same estate.

According to the 1900 Census, the residence on McCurdy was owned, not rented, but it was mortgaged rather than owned free.19 In the 1900 probate case file approving the sale of the property, a petition asserts that the entire family–James, Fannie, Joseph J., Charles, and the younger Campbell children via Charles’s guardianship–was beholden to an $800 mortgage held by one Benjamin Atkinson.20 I don’t know for sure yet (I need to find the Campbell-Atkinson mortgage deed, presuming one exists) but I’m guessing the mortgage with Benjamin Atkinson was executed in about 1897, and was the reason Charles became guardian of his minor siblings’ estate that year.

As for why the actions on Mary’s estate didn’t begin until nine years after her death: so long as the family was living on the property and not attempting to refinance or sell it, then there was no reason to get the courts involved.

In September 1900, the Campbells sold the McCurdy Avenue property to Mary Hawkins, apparently to wriggle free from the Atkinson mortgage. The sale of the lot and house that was the Campbell family home for seventeen years generated a deed which is a treasure trove of genealogical data, linking the entire family together–including Charles’s wife Inga and the tragically deceased Mary Christina (Nagle) Campbell.

Well, almost the entire family. But I’ll get to that in Part Five.

Although James immediately turned around and purchased a lot on Elroy Street from Mary Hawkins23 after the sale of the McCurdy Avenue property, he doesn’t appear to have ever lived on Elroy Street.

By the time James filed the paperwork to become administrator of Mary’s estate in late August 1900, he was living at 2017 Nelson Street (see his application, above). Charles and Inga lived at 2017 Nelson Street when they were enumerated for the 1900 U.S. census earlier that year,24 so it seems James, Fannie, Martha Jane, and William moved in with Charles and Inga sometime in mid-1900.

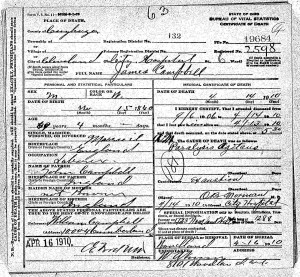

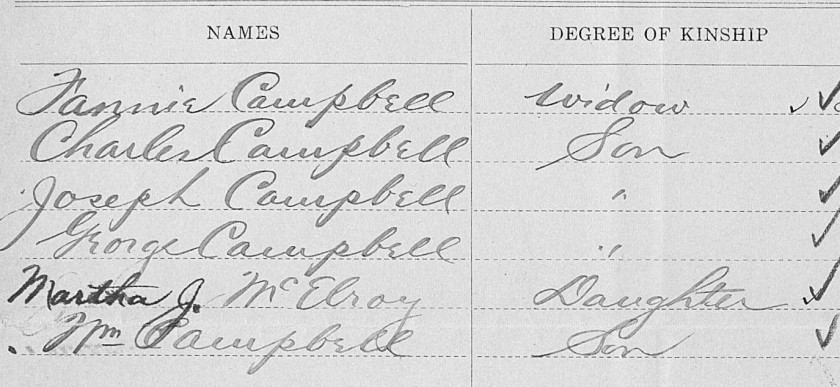

James purchased the Elroy Street property in his name alone, perhaps to avoid the hassle of a probate case involving the entire family should he want to sell. If so, his attempt was in vain because when James died in 1910, Mark McElroy (the administrator of James Campbell’s intestate estate) had to go ’round and get the entire family’s approval to sell the property back to Mary Hawkins and give the proceeds of the sale to Fannie.25

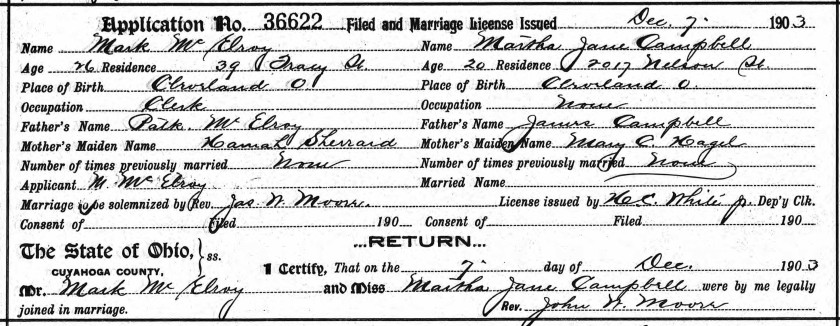

As I mentioned in Part Three, Mark McElroy was Martha Jane/Jennie’s husband, and they were married on 7 December 1903. Note Martha Jane’s residence, 2017 Nelson St.

Later that month, George W. Campbell married Mahala J. Wilson on 31 December 1903.27 Joseph James Campbell married Ellen Viola Mattern in Butler, Pennsylvania earlier that year, on 10 June 1903.28 By the time 1904 rolled around, only youngest son William Ernest remained unmarried and living at home.

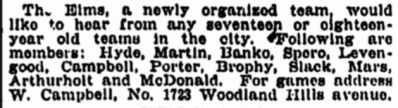

In 1904, home for William was 1723 Woodland Hills Avenue, which is the address James Campbell’s 1910 death certificate noted as his last home address before he was hospitalized long-term due to Parkinson’s disease.29 It’s also the address William provided as contact information in his Plain Dealer amateur baseball notices.

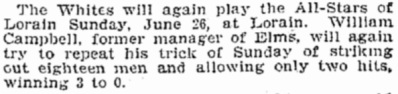

Turns out William had at least one pretty amazing outing on the mound, by the way:

In September 1904, Charles and Inga Campbell lost a nine-week-old baby girl to entero colitis32–just two years after they lost a nine-month-old son to cholera in August 1902.33 Both little ones were buried in section 76, lot 51 of Woodland Cemetery–the same cemetery where Mary Nagle Campbell was buried in 1888,34 but not the same plot.

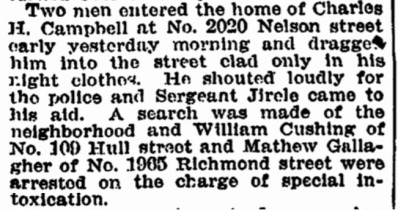

As if losing two babies within two years wasn’t enough, Charles was the victim of a home invasion (and possibly an attempted kidnapping or beating) in late August 1905:

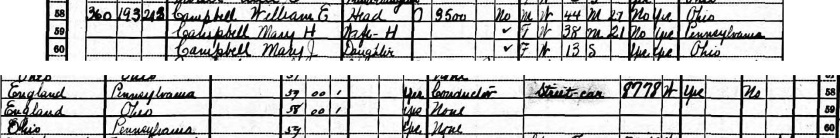

In the midst of all that, Charles seems to have had difficulty finding a steady occupation. He’s a “wiredr” (sic?) in the 1902/03 directory,36 and a finisher in 1903/04.37 The 1904/0538 and 1905/0639 Cleveland City Directories list him as a millworker. He’s a wireworker in 1906/07,40 then an ironworker in 1907/0841 and 1908/09.42 By 1909/10, Charles (H) Campbell of Nelson Street/Avenue disappears from the Cleveland Directory,43 then reappears on the 1910 U.S. Census living in…Los Angeles. Working as a street car conductor.44 Sound familiar?

It seems both Charles and William headed west to Los Angeles and got into the street car business in about 1909. Charles remained in Los Angeles until his death in 1961.45 He was a street car conductor until at least 1920,46 but by 1930 he was a yard worker in a woodshop.47 By 1940 he was a carpenter, like his father.48

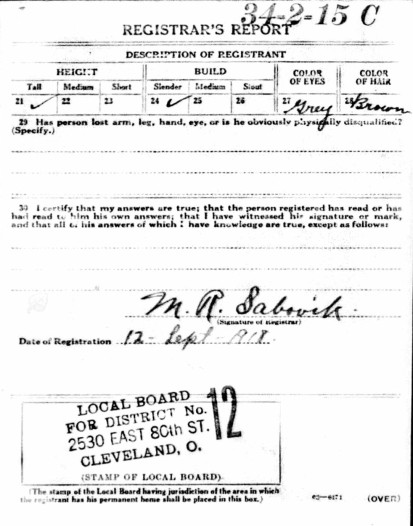

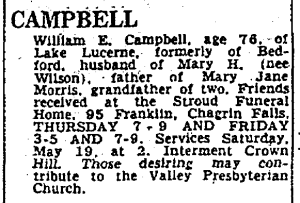

William came back to Cleveland and became (perhaps after learning the trade out in L.A. with his brother) a street car conductor, an occupation he remained in until his retirement.49 In January 1910, William told the county clerk that Los Angeles was his residence when he applied for a license to marry his first wife (my great-great-great grandmother) Evelyn McEachern, daughter of William McEachern and Evelyn Endean.50

Endean.

En-dean.

N-Dean.

N. Dean.

Now, where have I heard that before?

Oh yeah. James Campbell married Fannie N. Dean.

But wait, when Fannie died in 1914, the father listed on her death certificate was “William Gill.”

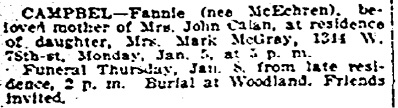

And her obituary claimed her maiden name was McEchren.

So was she Fannie N. Dean, Fannie Gill, or Fannie McEchren? Was “N. Dean” supposed to be Endean? Was “McEchren” an alternate spelling of McEachern? And what’s with William’s ex-wife’s parents’ surnames showing up in records about his stepmother?

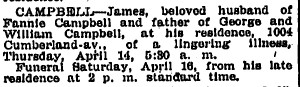

Mrs. Mark “McGray” is a typo. Mrs. Mark McElroy lived at 1344 W. 78th Street.53 Fannie died at her stepdaughter Martha Jane (Campbell) McElroy’s house, but hold up–the obituary also says Fannie was the “beloved mother of Mrs. John Calan.”

Didn’t a Mr. John Callan live with William Ernest Campbell and his second wife Mary in 1920?54

You’re probably starting to get why I call this Cleveland cluster a Gordian knot.

And now, the recap:

Was William Campbell’s mother from England? Or was she from New York, or Pennsylvania?William Campbell’s mother, MaryC.Christina Nagle, was born in New York.Was Fannie Campbell actually William’s biological mother?No, she was not. She was his stepmother.- Did Fannie have ten children, two of whom survived, or six children, all of whom survived?

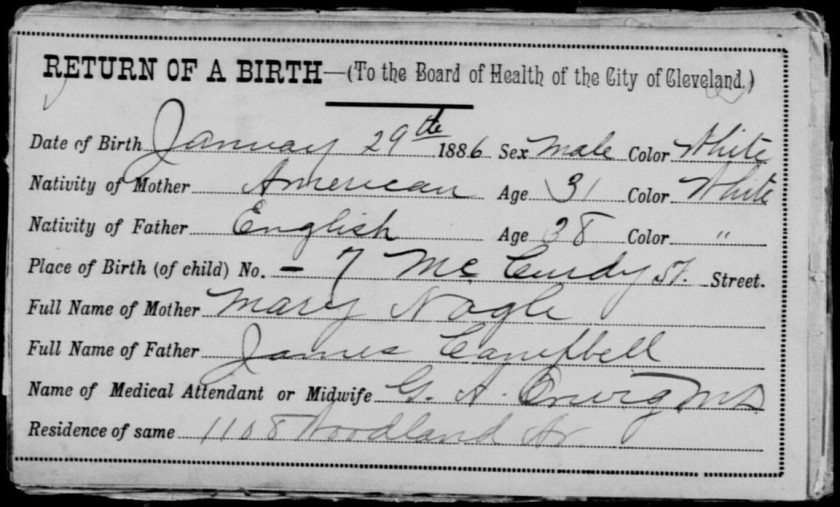

When exactly was William E. Campbell born? (The smaller fluctuations in his age from census to census might be resolved by comparing his birth month to the official census date, but other shifts are too large to be tidied up that way.)William Ernest Campbell was born to James and Mary (Nagle) Campbell in Cleveland, Ohio on 29 January 1886.Did Fannie Campbell die before 1920, or did she just move out?Fannie Campbell died on 5 January 1914.Are Eveleyin and Mary Campbell the same person?No. Evelyn I. McEachern was William’s first wife, Mary H. Wilson was his second.What were James and Fannie Campbell each up to before they got married in their thirties?James and Fannie were not married in 1881 as the 1900 census suggests. Before James married Fannie, he had a family with MaryC.Christina Nagle for fifteen years, until her death.-

What was William E. Campbell’s connection to Los Angeles, California?William’s brother Charles moved to Los Angeles and became a street car conductor in about 1909. It appears William accompanied his brother to California, then returned to Cleveland. If Fannie Campbell and Mary Naegel/Nagle are not the same person, what happened to Mary prior to 1900?Fannie and Mary were not the same person, and Mary died after complications from childbirth in 1888.When did James Campbell marry his second wife, Fannie?James Campbell married Fannie “N. Dean” on 14 June 1890.What was Fannie Campbell’s maiden name?(Dean, if the James & Fannie marriage record is to be believed. It shouldn’t be.)- What was Fannie up to in the years after her immigration and prior to her marriage to James Campbell?

What happened to the McCurdy Street property James purchased with Mary in 1883 and still owned in 1900?The family sold the property to Mary Hawkins in September 1900, after the census was taken.- Were any of the Campbell boys ever actually sent to the House of Refuge?

- Okay, seriously though, what was Fannie’s maiden name?

- Was Fannie somehow related to Evelyn McEachern?

- Who were Mr. and Mrs. John Calan?

See you in part five, when we finally find out about Fannie’s life before James, including the grisly suicide that made her a widow.

1. Margaret Crymes, “The Cleveland Gordian Knot (A Genealogical Puzzle), Part Three: James Campbell and Mary C. Nagle,” kinvestigations.com, 20 March 2018 (https://kinvestigations.com/2018/03/20/the-cleveland-gordian-knot-a-genealogical-puzzle-part-three-james-campbell-and-mary-c-nagle/ : accessed 19 March 2018), para. 16.↩

2. “A Precocious Bad Boy,” The (Cleveland) Leader and Herald, 30 May 1889, p. 8, col. 2; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831524378835 : accessed 2 April 2018).↩

3. “An Accomplished Liar,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 10 May 1889, p. 8, col. 2; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831524377939 : accessed 2 April 2018).↩

4. “An Incorrigible Boy,” The (Cleveland) Leader and Herald, 6 June 1889, p. 8 , col. 2; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831524378391 : accessed 2 April 2018).↩

5. “Missing Children,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 24 April 1890, p. 6, col. 6; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831524378391 : accessed 2 April 2018).↩

6. “WANTED situation by boy of 15,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 17 March 1889, p. 3, col. 6; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831524380702 : 2 April 2018).↩

7. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Marriage Records, 34:346, Campbell-Dean, 1890; database with images, “Ohio, County Marriages, 1789-2013,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939K-BP97-ZQ : accessed 25 April 2018), Cuyahoga > Marriage records 1889-1890 vol 34 > image 231 of 338;; citing microfilm of original records, Cuyahoga County Courthouse, Cleveland.↩

8. Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1890_United_States_Census), “1890 United States Census,” rev. 23:10, 15 April 2018.↩

9. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending July 1892 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1891), 144-145; image copy, Archive.org (https://archive.org/stream/clevelanddirecto1891clev#page/144/mode/2up : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

10. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending July 1896 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1895), 152-153; image copy, Archive.org (https://archive.org/stream/clevelanddirecto1895clev#page/152/mode/2up : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

11. John J. Grabowski, ed., Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (http://case.edu/ech/articles/s/street-names/), “Street Names,” accessed 30 April 2018.↩

12. “A General Kick,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 24 April 1894, p. 5, col. 4; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831524682638 : accessed 25 April 2018).↩

13. Cleveland Historic Maps (https://www.arcgis.com/apps/View/index.html?appid=ddb0ee6134d64de4adaaa3660308abfd : accessed 3 April 2018), toggle on the 1898 layer, search for “McCurdy Ave, Cleveland, Ohio.”↩

14. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Marriage Records, 44:74, Campbell-Simmons, license no. 12300; database with images, “Ohio, County Marriages, 1789-2013,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939K-BG9R-TB : accessed 25 April 2018 , Cuyahoga > Marriage records 1896-1897 vol 44 > image 80 of 300; citing microfilm of original records, Cuyahoga County Courthouse, Cleveland.↩

15. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, probate case file no. 16815, Minors of Mary Christine Campbell, guardian bond for Charles H Campbell; digital images, “Ohio, Cuyahoga County Probate Files, 1813-1932,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRPW-R15 : accessed 30 April 2018), Docket 48 > Case no 16786-16818 1897 > image 417 of 448; citing original records, Cuyahoga County Archives.↩

16. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Deed Book 355: 414-415, George and Margaretha Schraufl to James and Mary C. Campbell, 2 October 1883; database with images, Cuyahoga County Fiscal Officer (https://fiscalofficer.cuyahogacounty.us : accessed 19 March 2018), Recorded Documents > General Deed Search > use Book and Page fields, click through to download image files.↩

17. W.H. Whittaker, ed., The Annotated Probate Code of Ohio, Second Revised Edition (Cincinnati: W.H. Anderson & Co, 1897), 355, statue 6256; image copy, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hl49z2;view=1up;seq=371 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

18. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, probate case file no. 23327, Estate of Mary C Campbell, James Campbell application for letters of administration, 28 August 1900; digital images, “Ohio, Cuyahoga County, probate records, 1827-1924,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939N-GFKL-5 : accessed 30 April 2018), Estate files, docket 60, case no. 23299-23340, Jul-Oct 1900> image 366 of 478; citing original records, Cuyahoga County Archives.↩

19. Margaret Crymes, “The Cleveland Gordian Knot (A Genealogical Puzzle), Part One: William E. Campbell in the Census,” kinvestigations.com, 9 March 2018 (https://kinvestigations.com/2018/03/10/the-cleveland-gordian-knot-a-genealogical-puzzle-part-one-william-e-campbell-in-the-census/ : accessed 30 April 2018), para. 2.↩

20. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, probate case file no. 23386, James Campbell vs Charles Henry Campbell et al, petition 17 September 1900; digital images, “Ohio, Cuyahoga County, probate records, 1827-1924,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939N-GF7M-JM : accessed 30 April 2018), Estate files, docket 60, case no. 23379-23417, Jul-Oct 1900 > image 79-80 of 488; citing original records, Cuyahoga County Archives.↩

21. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Deed Book 761: 506-508, James Campbell [et al] to Mary Hawkins, recorded 5 October 1900; database with images, Cuyahoga County Fiscal Officer (https://fiscalofficer.cuyahogacounty.us : accessed 19 March 2018), Recorded Documents > General Deed Search > use Book and Page fields, and narrow by date, then click “Begin Search.”↩

22. Ibid.↩

23. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Deed Book 772: 201, Mary Hawkins to James Campbell, recorded 27 December 1900; database with images, Cuyahoga County Fiscal Officer (https://fiscalofficer.cuyahogacounty.us : accessed 19 March 2018), Recorded Documents > General Deed Search > use Book and Page fields, and narrow by date, then click “Begin Search.”↩

24. 1900 U.S. Census, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, population schedule, Cleveland City, Ward 26, p. 160 (stamped), ED 135, sheet 16-A, dwelling 250, household 282, Charles Campbell; database with images, “United States Census, 1900,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6P63-QQS : accessed 30 April 2018), Ohio > Cuyahoga > ED 135 Precinct C Cleveland City Ward 26 > image 31 of 35; citing NARA microfilm publication T623, roll 1257.↩

25. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, probate case file no. 56874, Mark McElroy vs. Fannie Campbell; digital images, “Ohio, Cuyahoga County Probate Files, 1813-1932,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YSL9-W73K : accessed 11 March 2018), Docket 93 > Case no 56837-56877 Apr 1911-Aug 1911 > images 379 – 398 of 529; citing original records, Cuyahoga County Archives.↩

26. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Marriage Records, 58:155, McElroy-Campbell, 1903; database with images, “Ohio, County Marriages, 1789-2013,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939K-BP9P-FP : accessed 25 April 2018), Cuyahoga > Marriage records 1903-1904 vol 58 > image 125 of 302; citing microfilm of original records, Cuyahoga County Courthouse, Cleveland.↩

27. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Marriage Records, 58:217, Campbell-Wilson, 1903; database with images, “Ohio, County Marriages, 1789-2013,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939K-BP9R-7Z : accessed 25 April 2018), Cuyahoga > Marriage records 1903-1904 vol 58 > image 156 of 302; citing microfilm of original records, Cuyahoga County Courthouse, Cleveland.↩

28. Butler County, Pennsylvania, Marriage Docket Book 15:172, Campbell-Mattern, 1903; database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VF9V-5V1 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

29. Crymes, “The Cleveland Gordian Knot (A Genealogical Puzzle), Part Three: James Campbell and Mary C. Nagle,” para. 1.↩

30. “Among the Amateurs,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 2 April 1904, p. 6, col. 2; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831525121370 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

31. “Among the Amateurs,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 21 June 1904, p. 8, col. 8; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831525122397 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

32. Cleveland Department of Parks and Public Property, Division of Cemeteries, Woodland Cemetery Interment Register 5-6:140, no. 45177, Baby Jas. Campbell, 11 August 1902; database with images, “Ohio, Cleveland Cemetery Interment Records, 1824-2001,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9TDQ-QWZ : accessed 30 April 2018), 004466573 > image 143 of 208; citing digital images of originals, Department of Parks, Recreation and Properties, Cleveland, Ohio.↩

33. Cleveland Department of Parks and Public Property, Division of Cemeteries, Woodland Cemetery Interment Register 7-8:36, no. 49015, Baby Campbell, 16 September 1904; database with images, “Ohio, Cleveland Cemetery Interment Records, 1824-2001,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9TDQ-QQZ : accessed 30 April 2018), 004466575 > image 39 of 194; citing digital images of originals, Department of Parks, Recreation and Properties, Cleveland, Ohio.↩

34. Crymes, “The Cleveland Gordian Knot (A Genealogical Puzzle), Part Three: James Campbell and Mary C. Nagle,” para. 17.↩

35. “Free Bath For A Hold Up Man,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 29 August 1905, p. 14, col. 1; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831525148111 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

36. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending July 1903 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1902), 201; image copy, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112033564714;view=1up;seq=189 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

37. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1904 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1903), 201; image copy, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112033564722;view=1up;seq=191 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

38. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1905 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1904), 212; image copy, “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/2469/4160752#?imageId=4160851 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

39. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1906 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1905), 213; image copy, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t2z35f63g;view=1up;seq=207 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

40. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1907 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1906), 260; image copy, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112033564755;view=1up;seq=254 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

41. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1908 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1907), 235; image copy, “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/2469/4147909#?imageId=4148030 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

42. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1909 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1908), 237; image copy, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112033564771;view=1up;seq=227 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

43. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1910 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1909), 225; image copy, “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/2469/4155454#?imageId=4155561 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

44. 1910 U.S. Census Los Angeles County, California, population schedule, Los Angeles City, Precinct 206, p. 93 (stamped), ED 251, sheet 6-A, dwelling 139, household 147, Charlies (sic) H. Campbell; database with images, “United States Census, 1910,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RVP-XY4 : accessed 30 April 2018), California > Los Angeles > Los Angeles Assembly District 70 > ED 251 > image 11 of 22; citing NARA microfilm publication T624, roll 81.↩

45. “California Death Index, 1940-1997,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VGT2-SX1 : 30 April 2018), Charles H Campbell, 08 Jul 1961; Department of Public Health Services, Sacramento.↩

46. 1920 U.S. Census, Los Angeles County, California, population schedule, Los Angeles City, Precinct 603, p. 71 (stamped), ED 289, sheet 9-A, dwelling 164, household 212, Charles H. Campbell; database with images, “United States Census, 1920,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RXR-48 : accessed 9 March 2018), California > Los Angeles > Los Angeles Assembly District 71 > ED 289 > image 17 of 37; citing NARA microfilm publication T625, roll 111.↩

47. 1930 U.S. Census, Los Angeles County, California, population schedule, San Antonio Township, Florence Precinct, p. 140 (stamped), ED 1367, sheet 4-B, dwelling 104, household 104, Charles H. Campbell; database with images, “United States Census, 1930,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9R4T-CRJ : accessed 30 April 2018), California > Los Angeles > San Antonio > ED 1367 > image 9 of 52; citing NARA microfilm publication T626, roll 172.↩

48. 1940 U.S. Census, Los Angeles County, California, population schedule, San Antonio Judicial Township, Florence, p. 11787 (stamped), ED 19-630, sheet 3-A, household 96, Charles H. Campbell; database with images, “United States Census, 1940,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MT-XQZY : accessed 30 April 2018), California > Los Angeles > San Antonio Judicial Township > 19-630 San Antonio Judicial Township (Tract 515 – part) bounded by (N) Florence Av; (E) Hooper Av; (S) 76th; township line; also Florence (part) > image 5 of 24; citing NARA digital publication T627.↩

49. Margaret Crymes, “The Cleveland Gordian Knot (A Genealogical Puzzle), Part Two: The William E. Campbell Vitals,” kinvestigations.com, 10 March 2018 (https://kinvestigations.wordpress.com/2018/03/10/the-cleveland-gordian-knot-a-genealogical-puzzle-part-two-the-william-e-campbell-vitals/ : accessed 19 March 2018), para. 2.↩

50. Ibid, para 5.↩

51. Ohio Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Death no. 1166, Fannie Campbell, 5 January 1914; “Ohio Deaths, 1908-1953,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GPJ5-S34Q : accessed 30 April 2018), 1914 > 00001-03000 > image 1351 of 3345; citing digital images of originals, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus.↩

52. “Campbel,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 8 January 1914, p. 14, col. 1; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://www.genealogybank.com/nbshare/AC01150128074204280831525206268 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

53. The Cleveland Directory, Year Ending August 1915 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co, 1914), 1004; image copy, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112033564839;view=1up;seq=998 : accessed 30 April 2018).↩

54. Crymes, “The Cleveland Gordian Knot (A Genealogical Puzzle), Part One: William E. Campbell in the Census,” para. 9.↩